BEING A RELATIVE of Eddie Guerrero means that at certain moments and for particular reasons, recollections of the famed wrestler will come flooding into your mind. Maria Guerrero's memories are filled with the sounds of slaps across the chest, the grunts of pretend pain, and of bodies slamming against each other. From the backyard of her childhood home, neighbors heard a father teaching his sons the family business. "You're doing it wrong!" Gory Guerrero would shout.

Maria is drinking coffee inside a restaurant about a 10-minute drive north of the U.S.-Mexico border. She searches inside a manila folder and talks about things that happened long ago. Depending on what memory she pulls from her mind or from the folder, her expression changes between smiling eyes and a straight face. "We lived on Huerta Street," Maria says.

She's the last of the Guerreros in the city synonymous with their name, talking of where they all once lived. That single-story brick house in the Buena Vista neighborhood was a God-fearing home. It was three blocks from the border separating El Paso, Texas, and Jurez, Mexico, and a five-minute drive from the El Paso County Coliseum where the family spent most of their time. "We came to El Paso in 1962," Maria explains. Her father was Gory, the patriarch of her legendary family who started wrestling at 16. When the fighting part of his career declined with age, he brought his family here. "My father liked that it was both Mexican and American," she says.

Wrestling had been a staple of El Paso entertainment since the 1920s. Those shows with masked men would eventually birth the Mexican style of wrestling called lucha libre. Then a growing city, El Paso relied on the so-called five C's -- copper, cotton, cattle, climate and clothing -- to power its economy. Gory had always focused on the business side of wrestling. Monday night shows at the county coliseum, other nights in surrounding areas that would have them. From making sure wrestlers had whatever they needed -- like sports tape to hide razor blades affixed to their wrists -- to making popcorn for concessions, everyone in the Guerrero family had a job. Never far from being inside the ring, Gory also passed what he knew to his sons. "We had a wrestling ring in the backyard," Maria says. "That's where my father trained my brothers."

The choreographed violence inside the ring is a delicate mix. When a single inch makes all the difference, every step and hold must be as close to perfect as possible. Too much distance between fiction and reality and it's not believable. "This is Chavo Sr. and Mando," Maria says of a black-and-white photo from some time in the 1960s. Her younger brothers are in the backyard, practicing leg locks while her father watches and points.

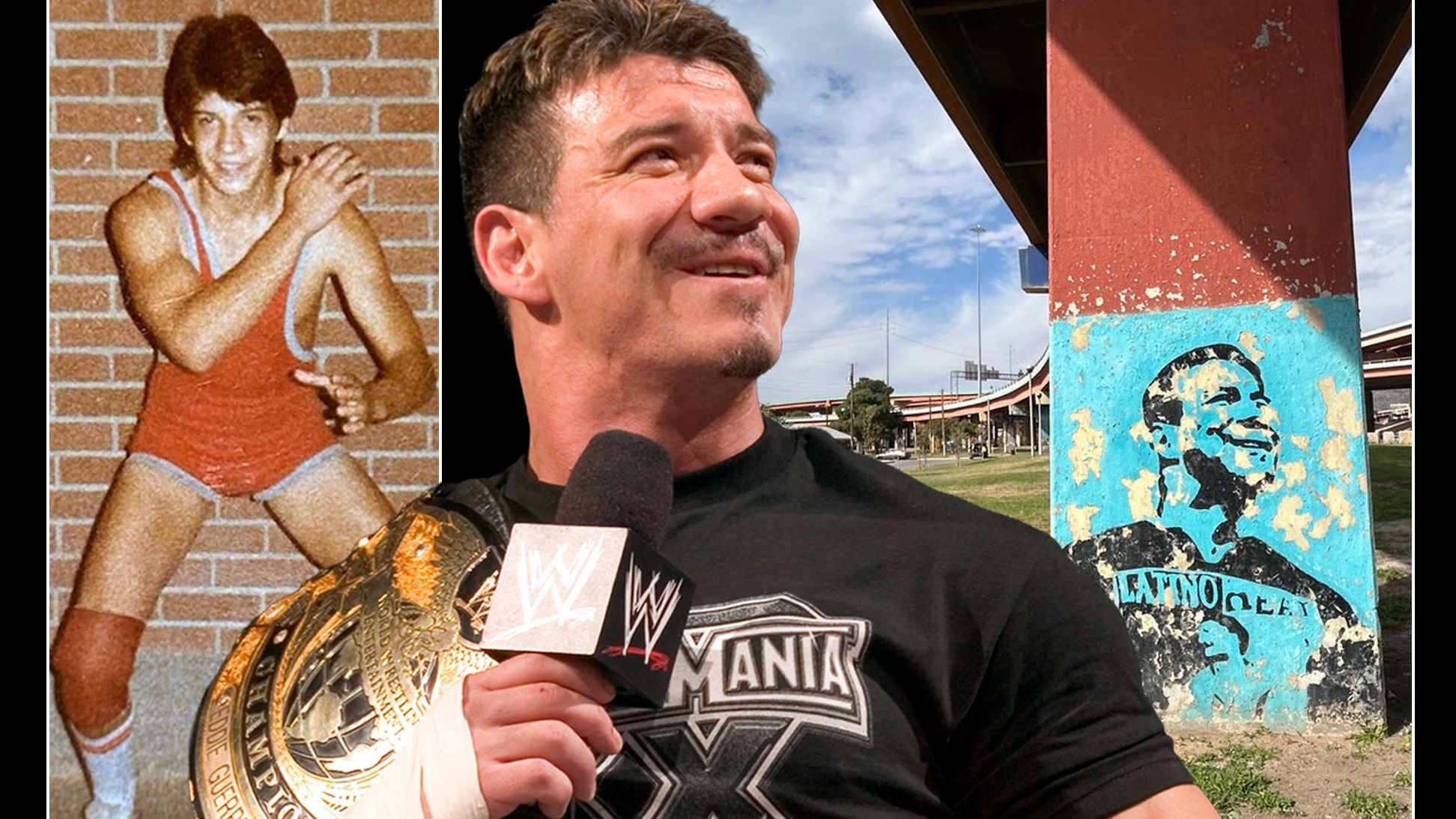

They were the first two Guerrero boys. After them came Hector, Eddie, and even Gory's grandson, Chavo Jr. All of them learned to wrestle inside that ring. Another colorless photo and Maria points to its top right corner. "This is Eddie as a baby," she says. It's a family photo with Gory, his wife, Herlinda -- who knew the business as well as anyone since her three brothers wrestled in Mexico -- and their four sons and two daughters. Gory is carrying Eddie. He was by far his youngest child, so it looks more like a grandfather holding his grandson.

"My aunts in Mexico thought he was mine, and that my family was covering it up," Maria laughs as she remembers the brother nearly 21 years younger than her. Those memories brighten her eyes. She can still see him as a young boy -- Ewis, they called him -- playing inside the ring in the backyard of their home.

Her voice fills with pride when talking of how Eddie carried the Guerrero name as high as it could go and how people still remember him though he has been gone for 20 years this month. "He would have been 58 right now," Maria says of Eddie. On the morning of a show in Minneapolis, Eddie died of a heart attack while brushing his teeth in a hotel bathroom. "He was about to retire," Maria continues.

A moment of quiet as we sit across from each other with pieces of the past in front of us. "He's still very present," Maria says. A sip of coffee and another search. She then slides Eddie's funeral program halfway across the table.

"THAT'S GORY'S SON," my grandmother told me the first time I saw Eddie.

I was around 7, the age when a stranger's presence can bury itself into a malleable mind. Until then, I didn't know who Eddie was. But I knew Gory because during my summers spent with my grandmother in Jurez, she'd tell me stories about him.

She'd talk about lucha libre, explaining how its characters could be good or bad, the babyfaces or heels. That some of the masked men carried on the names of those long before them. How Gory helped popularize lucha libre across Mexico as its most famous non-masked wrestler. That, when she was a little girl, he was the tag team partner of El Santo, one of the most famous grapplers of them all. She told me Gory was so great as a heel he needed a police escort to protect him from fans who wanted to hurt him.

Her love of wrestling made her scream obscenities at the heels inside Gimnasio Municipal Josu Neri Santos. The gym with faulty plumbing and bad lighting was in downtown Jurez, a half mile south of the border. Years later, Konnan, Eddie's former tag team partner, remembers the gym also lacked security. "I turned heel, against Eddie of all people, and the fans were super pissed," he says. "They threw everything from dirty diapers to battery acid at me," he adds. "It was just a very rabid fan base, which is what you want."

Inside that gym is where I spent a lot of my time during the summers, when my parents were working an eight-hour drive north in Colorado. I still remember how my mother cried the first time we moved there. She tried to console us but especially herself, by telling us to enjoy the state's natural beauty. Green and cold, it was the opposite of the desert we came from.

From the moment I saw him, I knew Eddie was different. Some of the other wrestlers were older with receding hairlines that couldn't hide the scars on their foreheads from getting sliced with razor blades. They carried the hurt from the countless times they got body-slammed. They looked unbalanced whenever they limped to the ring's top rope. Unlike them, Eddie's body and skin weren't scarred. At 19 years old, he moved with the confidence of youth. Athletic and acrobatic, whenever he climbed to the top rope, he'd stand there gracefully for everyone to see.

When he jumped and his long black hair flowed in the air, it looked like Eddie could fly. It also looked like what evolved into the Frog Splash. That was Eddie's signature move where he'd jump from the top rope, tuck his knees to his chest, then uncoil as he landed on an opponent.

With that move he would become the Eddie Guerrero the wrestling world would remember. The wrestler who once gave The Rock among the best matches he's ever had. The one who John Cena called a genius.

Every time he'd land the move that would later be known as the Frog Splash, I'd jump out of my seat, cheering along with everyone else.

"HE VISITS ME three, four times a year," Sherilyn Guerrero says about the dreams she has of her father. She's Eddie's middle daughter. Just 10 years old when she last saw him walking into Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport.

Sherilyn liked to playfully wrestle with Eddie. They'd wrestle in their living room and sometimes in the ring before his matches. He'd tell her stories of his own father, who died before she was born, and the family they came from. Wrestling felt natural to her, so innate that Sherilyn is now training to be a wrestler, too.

"They've never been sad," she says of her dreams.

Family members have told her they've also dreamed of Eddie. Sometimes they wake up confused, trying to understand why they can't see his face. But with Sherilyn, each of those dreams feels like a blessing. If they come during difficult times, she is convinced it's him telling her everything will be all right. "He was a great father," Sherilyn says.

Some kids called in sick to school for legit reasons. Sherilyn's sick days were often excuses to travel with dad. Most kids spent spring break at home, but Sherilyn and her older sister, Shaul, along with their mother, Vickie, spent that time at WrestleMania. "Your dad is so cool," classmates would tell her when she returned.

A genuine connection between a wrestler and fans is one thing the business can't script, and Eddie had it. Her father could make the crowd love or hate him, sometimes in the middle of matches as he switched between babyface and heel. The "Latino Heat" character he created from the people and places he came from was impossible to ignore. He'd yell "Viva La Raza!" as a catchphrase, speaking in Chicano slang, and drive lowriders up to the ring. Bordering on slapstick comedy, he was even funny in how he'd frame opponents when the referee wasn't looking.

It felt good to hear classmates talk of her father, but that also made Sherilyn shy and guarded. She wondered if people wanted to be her friend only because she was Eddie's daughter. To this day, when she meets someone around Houston, where she lives, she doesn't mention his name. But Eddie lives an immortal existence online, so they eventually find out.

"Every day someone's sending me something on my dad," Sherilyn says. Something as simple as tagging her social media with a clip of Eddie's wrestling highlights. Other times it's messages from those who've made art inspired by him.

"His spirit is so alive," Sherilyn says. She admits that everything has made it difficult to process he's gone. He was home for just a couple of days each week, so part of Sherilyn feels like her father has still been on the road. That eventually he'll call with the time his flight arrives at the airport. While she waits, a part of Sherilyn has yet to fully mourn.

"What happens the day I do?" she asks herself, wondering how she'll feel when that moment comes. It's been difficult to get there when she sees him every day, even if it's the fictional part of who he was. That's why those three or four dreams a year feel like a blessing. In those dreams where the two of them play, she's with a side of Eddie most didn't know. She tells me about those dreams, and I feel guilty for asking if she can tell me more. Like I've opened a door to a visiting room where I don't belong. But rather than leave, I stand there and watch with that familiar feeling of being a stranger.

THE FIRST DREAM I ever chased was being a wrestler. I was 7 and spending the summer in Jurez designing a mask and a matching cape. I'm certain I also made up a name. I don't remember it so it must have been bad.

What I do remember is how I'd slap myself across the chest, throw myself against a wall, fighting someone who wasn't there. I'd jump on beds in my grandmother's home, pretending I was flying off the top rope, stopping only after breaking one of them. I was trying to replicate the moves I saw during the Thursday and Sunday shows I attended. I'd try to memorize what I saw in the ring, then a day or two after, I'd pick fights with uncles just to have someone to practice against.

They were much older and stronger, they'd go along with my game until they got annoyed and the play wrestling turned real. Once I'd get body-slammed and struggled to breathe, it was time to leave them alone.

Years later I'd pursue other dreams, each of them an empty search. But long before then, I imagined myself as a wrestler in Jurez and the reason was Eddie. I wanted to wear a mask and cape and be anyone who didn't have to feel the summer end. I didn't want to return to feeling like a stranger; the boy who spoke with an accent in that green and cold of Colorado.

THERE'S A TRAILER parked on the plot of land Mando Guerrero owns. Since it's the middle of July and that land is in a small Texas town between San Antonio and the Gulf of Mexico, it feels like breathing inside a sauna.

"It's not set up," Mando says of the pieces of metal resting atop the trailer. "It's our ring."

He can't remember the last time it was fully built so he has been thinking of assembling it. But at 75 years old it's not as easy as it once was for Eddie's oldest living brother. Not when he feels the toll of a physical life, first as a wrestler around the world, then as a stuntman and coordinator in Hollywood. It's hard enough to walk with prosthetic knees without having to carry heavy pieces of metal.

"I want to see what's left," Mando says, curious about what remains of the ring that was once in their backyard and traveled wherever they promoted a show. "We were like a circus," he remembers. "We would come in, set it up, and break it down" he says. "That's what we were, a circus. And the 'Wrestling Guerreros' was our name.

"Family was the most important thing so Gory took them on the road with him. He'd tell his children everything was all right when they watched him bleed. Other times he'd tell them to sit in the stands but never mention they were his children, worried they'd be hurt by those who refused to distinguish what's real from what's staged.

"It has sentimental value, but there's really nothing I can do with it," Mando says of the ring. It's where all the Guerreros learned to wrestle and its canvas -- parts of which he's sure rats have eaten away -- is stained with the blood and sweat of his father and brothers.

Mando has a stepdaughter who lives in Minneapolis. He loves her but laments not having children of his own. Maybe they'd be here to help rebuild the ring. Maybe they'd be here to learn all the things he got from his father.

"We represent something that was a phenomenon in the game of professional wrestling," Mando says with a prideful tone. He's protective of the family name especially when talking of his baby brother. He isn't alone. Some who knew Eddie the best would rather let what remains of the family legacy speak for itself.

"Eddie was a natural," Mando says of his brother, who was inducted into the WWE Hall Of Fame in 2006. He explains how Eddie took everything he learned from his father and three older brothers, mixed it with the high-flying acrobatics of Mexican lucha libre as well as the wrestling style north of the border that relied on storylines and brute strength, and from that he created something of his own. In that way, Eddie benefitted from being the youngest of them all, but Mando says that also had its negatives. Because when family saw Eddie struggling with painkillers and alcohol, the baby of the family refused to even listen when they tried to help.

"He just wanted to be left alone," Mando says of Eddie during those years when he navigated his own personal desert. That all came after a nearly fatal car crash during the early hours of New Year's Day, 1999. Driving impaired, the crash left Eddie with a fractured collarbone, broken hip socket, lacerated liver, a shredded calf, and compressed discs in his spine. Painkillers and alcohol eased the hurt. Add to that the pain that came inside the ring -- the broken fingers and toes, blown-out knees, and backs that never recover once they go bad -- and Eddie was soon taking any pill he could get along with drinking more.

"Do you remember the last time you spoke with Eddie?" I ask. Mando makes a deep sigh and thinks. Though they sometimes spoke on the phone, he struggles to remember the last time he saw him. Eddie was on television so often, it mixes with the moments of seeing him in person. "I don't recall," he says.

ON NOV. 13, 2005, the phone rang and my mother answered. "Roberto," she said after the short call. "Your grandmother said Eddie Guerrero's dead." That memory is clear. And likely because I was dealing with my own struggles, I don't remember feeling much.

On the day Eddie died, I was a 25-year-old who had barely graduated high school and was bouncing around between a series of construction jobs. I slept on a broken futon with a thin mattress that left my back sore. Whatever dreams I had then felt as broken as where I slept.

Back living with my parents, I was depressed and ashamed from feeling like I'd wasted the opportunities they'd struggled to give me. I was lost, living between Phoenix, Tucson, and El Paso. And on each of those long, quiet drives through the lonesome deserts connecting those cities, I wondered why I was in the middle of losing an entire decade of my life, searching for what I couldn't find.

I stopped watching wrestling long before Eddie died. But in between the time I first saw him and when he died, I kept an eye on him as he won tag team, European, United States, Intercontinental and WWE championships. On the occasion I'd see him on television it always felt like reconnecting with an old friend even if he looked different. With about 220 pounds of muscle on his 5-foot-8 frame, Eddie had a larger presence than he ever had in Jurez. Not just physically, but also as a character since his confidence and charisma had also grown. But he was still the same Eddie who made me feel that warm sense of pride whenever he got introduced as being from home.

"I was very proud of Eddie, too," Hector Rincon would tell me years later. Best friends since they were teenagers, their wrestling photos are next to each other in the 1985 Thomas Jefferson High School yearbook. Fighting as Hurricane Hector, Rincon also pursued dreams of professional wrestling until the time away from his family became too much. In some ways, he lived his dreams through Eddie. When Eddie won the WWE Championship in February 2004, Eddie called Rincon from the locker room and they cried together. "Nov. 13 is a bittersweet day," Rincon says. "He passed on the same day as my daughter's birthday."

I almost feel ashamed to admit it, but there was no overwhelming sadness when I heard Eddie died. There was no sense of disbelief, no contemplation of my own mortality. No proper understanding that Eddie was one of the few to make it out of here, then, at his peak, he was gone. It was like he had climbed to the top rope, jumped and flew away before I could fully understand why he meant so much to me.

All of that took years to find.

"I FELT EVERYTHING was OK," Dean Malenko says. His gruff voice can't hide the pain when talking of how unexpected Eddie's death felt. They were close friends even if they wrestled as bitter rivals inside the ring dozens of times.

Practically inseparable since they met in 1993 while wrestling in Japan, they had an instant connection as the youngest sons of heels. Dean's father was Boris Malenko. He played the role of Soviet agent so well that Malenko's friends were afraid to visit their home. Malenko and Eddie also bonded over their lifelong love of professional wrestling, both knowing from an early age that it would be the dream they'd pursue.

Across different promotions -- ECW, WCW and WWE, among them -- their careers grew together. They were travel partners navigating the unseen world of their profession. "The easiest part of our business is the wrestling," Malenko says. The difficult parts are the politics born out of something that relies on emotion. But more than that, it's the loneliness of being on the road and how quickly it can spiral out of control."

The wrestling life is being in one city then on to the next as soon as a match ends. That life continues over and over, year after year.

"There's horror stories of the guys that passed away in their hotel rooms," Malenko says of the life that's violent, grueling, and often short. On the road, traveling the unseen parts of the profession is also where Malenko began to worry about his friend.

"Eddie wasn't one to hide stuff," Malenko says. By his own admission, Guerrero was an angry drunk who'd fight anyone. At first, those occasions were a funny story to tell. But when those instances went from once or twice every few months, to every week, to every day, Malenko recognized that his friend needed help. They were in the WWE in 2001 when Malenko told management that Eddie had a problem. "The worst thing to do is rat on a friend," Malenko says, "but I was trying to save the guy."

Years later, Jim Ross, the legendary commentator, then the senior vice president of WWE Talent Relations, recalled that moment on his podcast, "Grilling JR."

"I saw one of the greatest pro wrestlers in the world that we were about to lose if we didn't get our arms around his problem," Ross said of Eddie. "But in order for us to get our arms around his problem, he's gotta cooperate with us. He's gotta allow us to hug him."

Because of Malenko, the WWE ultimately sent Guerrero to rehab for four months. But it also fractured their friendship. "Eddie didn't want anything to do with me," Malenko says, still certain he did the right thing because by November 2005, things had changed. By then, Eddie was past the days of relapsing and getting fired by the WWE. Eddie had reconnected with his faith, apologized to friends and family, and renewed his marriage vows to Vickie. Things were going so well he even met the conditions for a return to the WWE, "clean and sober through testing," Ross said, and he even started to forgive his friend.

"I felt like we didn't have to worry anymore," Malenko says. "Which made his death even harder."

The Hennepin County medical examiner said Eddie died of heart disease. Past use of painkillers, alcohol and steroids hardened and narrowed his arteries. In the days before he passed, Eddie would close his eyes and nod away during conversations. It looked like he was sleeping so friends and family thought he was just tired from the road. They later understood that was his heart slowing down, until it stopped inside Room 3015 of the Minneapolis Marriott City Center.

Three months after he passed, with the shock of one of its biggest stars gone at 38, the WWE implemented a random drug-testing policy.

"I miss him," Malenko says. "Eddie was like my little brother." He still watches their old matches even if it hurts. "They remind me of how much he meant to me as a person," Malenko says of those fights.

A FEW YEARS after I dreamed of being like Eddie, I watched Julio Csar Chvez knock out Meldrick Taylor in the last seconds of a fight. The way my father -- a strong, stoic man -- hugged me as it happened, you would have thought we'd just seen a miracle. That's when I wanted to box. That lasted until I got punched in the face a little too hard.

In my early teenage years, I was sure I'd play college football. I even taped a photo of the Heisman Trophy to the ceiling directly above my bench press for motivation. Then I stopped growing early in high school.

In my early-to-mid 20s, I sought more realistic things. They weren't dreams but ways to survive and get out of working construction. I wanted to be a mechanic like my father or sell bootleg CDs and DVDs at the swap meet like my uncle. I wanted to work at the copper mine or as a city maintenance worker since that provided medical insurance.

I was 28 years old when I wanted to be a high school teacher since that was the profession of my future wife. I took the El Paso Community College placement exam and almost didn't return after scoring a zero on the writing section. I enrolled and have rarely felt the self-doubt I had on that first day of class. I sat close to the door in case I wanted to leave since I was afraid that I was too old. Afraid I was wasting my time. Afraid of what came next if this also didn't work.

I forced myself to stay in that uncomfortable space of being a stranger again. Around books and between a struggling life, I was surprised to find I wanted to be a writer. That took me years to pursue, afraid I'd fail at that too. But I chased that dream. I wanted to tell stories, like the ones my grandmother had told me, of people in places important to me.

That's why I wanted to write about Eddie. I tried to for years, but I didn't know how. Until one day it hit me like a moment of clarity. The realization that if I was going to write about someone who isn't here, it had to be a story of how they exist in the space between reality and fiction. And what those memories mean to those who still love him.

MOST OF WHAT Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero knows of her father comes from the memories of others. From her mother, Tara, who tells her stories about the man she loved, from the friends who used to wrestle with him, and from aunts and uncles who tell her about their little brother.

"I'm the youngest daughter," Kaylie says. "I was only 3 when he passed."

Since she was a toddler, Kaylie has a couple of memories of her own but not much more. There's the one of Eddie singing and playing "The Name Game" where Eddie would say her name and alter it as he sang. And the one where she and her two stepsisters are at a store with him.

"I was in a shopping cart," Kaylie says. Eddie was at the height of his fame, trying to avoid attention. "He's telling my sisters, 'Don't mess around with the cart, you're gonna flip her over,'" Kaylie says. She remembers falling to the cold floor. She wasn't hurt but cried from being startled. And since others stared, she remembers the look of shock and embarrassment on her father's and stepsister's faces.

"For some reason that memory makes me laugh," Kaylie says. "He's just being an average dad going to the store. He's just trying to get what he needs and his daughters are causing a scene." As she shares the memory with me in the same way others have shared theirs with her, she can't help but to laugh some more.

In search of memories and connections, she finds comfort in their similarities. Things like their October birthdays being only three days apart. Or the gold and diamond necklace Eddie gave to her mother that she wears when she wants to feel close to him. Earlier this year, Kaylie attended a wrestling show at the El Paso County Coliseum. She got to be inside the place where her father spent most of his childhood. Back in his hometown, which will soon proclaim Nov. 18 as Eddie Guerrero Day, she even visited the murals dedicated to him.

"It was beautiful," she says of the fading mural under the bridge connecting the border between El Paso and Jurez. It has become a place of pilgrimage where people pull off the road to stop and pay their respects. Next to Eddie's mural is another one of the Wrestling Guerreros.

"There's this interview," Kaylie says of the video she found on YouTube as part of her search. It's an hour and 48 minutes long and it's just Eddie. Not the man who looked larger than life on television. It's just Kaylie's father speaking honestly about his struggles, his family and wrestling. "It's like he left it as a time capsule for me," Kaylie says of the interview she'll watch as often as she needs.

She'll watch to see his mannerisms and similarities between their faces. To see his smile and hear him say, "Follow your heart" when asked to give advice.

Every time she sees it, Kaylie feels like her father is talking directly to her.

WHEN YOUR FIRST sports hero dies at an early age, it alters your perception of time. Because no matter how old you get, some part of you returns to childhood whenever you think of them. Until one day you're as old as they were when they took their last breath. That's when you feel that relationship change.

What began as a childhood wonder with masked men who looked like they could fly around the ring, evolved into a focus on Eddie. During a time when I lived in what felt like different worlds, he reminded me of home.

I don't remember when I started to wonder more about Eddie as a person and less about him as a wrestler, but it was long after then. Probably when I outgrew making heroes out of athletes.

Searching for the Eddie that wasn't on television, I looked in old yearbooks with broken spines inside his old high school and in the scraps of things once important. I walked into the memories and dreams of those who loved him. I searched where everything began. Driving down Huerta Street with the car windows down and radio off, I listened to see if the echoes of the Wrestling Guerreros were still there.

And what I found, as someone now seven years older than when Eddie died, was the realization of how young he was and how fast it goes. When yesterday I was a 7-year-old in an unfamiliar world, today I'm a father, trying to instill a confidence I lost when arriving in this strange place north of the border. And since Eddie represented much more than a wrestler, I now introduce him to my daughter.

We watch videos of Eddie wrestling in front of what feels like the entire world chanting his name. I show her videos of him talking in English and Spanish so she can hear that familiar accent of someone who lives between two places. We watch so my daughter can see how someone from here, a place that isn't growing anymore, made it there.

"Eddie was one of us," I tell her.

"THIS IS HIS place," Linda Guerrero Rodriguez says as we stand where Eddie rests.

It's a cemetery in Scottsdale, Arizona, not too far from where she lives and where Eddie spent some of his final years. The dry heat eased the chronic pain he felt from an 18-year career and nearly 1,500 matches.

"How often do you visit?" I ask.

"At least three times a year; his birthday, Christmas, and usually in the spring," Linda says. "And there's always something here."

Today, around a marker that reads Eduardo Gory Guerrero, there's a replica of a WWE Universal Championship belt, a small sombrero, a toy lowrider car, and a Mexican decorative skull left by those who remember the dead. Sometimes there are cards and letters where people write of how much Eddie meant to them. When he first passed, Linda and her mom would visit and read those letters.

Out of all the siblings, Linda and Eddie were especially close. They were the youngest and when the oldest Guerreros moved out -- Chavo Sr., Mando and Hector to pursue their wrestling careers and Maria to become a teacher -- only Eddie and Linda were left.

With that bond, Linda could tell Eddie the painful truths. That he was like a different person when he drank and abused painkillers. When he once stopped breathing and had to be rushed to the hospital, Linda was the one who yelled at Eddie from his bedside even when she was unsure if he could hear. The one who wanted to talk about his problems even when he didn't. In the grip of addiction he overdosed three times, went bankrupt, but more than anything, lost a decade's worth of time.

Conversely, Eddie talked with Linda about things he couldn't tell others. The pressure he felt carrying the Guerrero name. How he wondered if their father would be proud of who he had become. When his 12th attempt at rehab worked, Eddie told Linda he wanted to be open with fans about his problems.

"He had just gotten his four-year sobriety chip when he passed a month later," Linda says with a look of hurt in her eyes that turns to love. "His last four years were beautiful. He transformed back to my little brother."

"Our family was never the same," Linda says of Eddie's passing.

Linda holds a quilt as she speaks. Her friend made it from Linda's old wrestling shirts with Eddie's face on them that she just couldn't wear. She works as a flight attendant and every few months someone at the airport or on a plane will wear a similar shirt. Sometimes she'll tell them Eddie was her brother then they'll ask if she can take a picture with them.

"Why do you think so many fans still remember Eddie?" I ask.

"Because he was so honest with his crowd," she says.

From a lifetime around wrestling she knows that's always been the most important thing. That none of this works if it's too removed from reality. It just looks foolish if you can't feel what's inside the ring. And that ability to honestly portray what isn't real is what Eddie did better than anyone else.

Linda goes quiet, staring at what's left -- even if Eddie's presence remains in photos, dreams and memories. She's the one who tries to keep his daughters close to her family even when it's complicated.

The one who apologizes as she cries when two decades ago still feels like yesterday.